Signaling and leadership

It’s a common, even mundane situation, but I believe one of the most difficult interpersonal challenges leaders face.

Imagine a leader walking into their office first thing in the morning to realize that an urgent and important issue has reached a crescendo and must be addressed right away. Sinking deeper into their chair, as their pace of thinking quickens, the leader sifts through various data sources – a trail of email memos, notes recounting a history of charged discussions with other executives, memories of feeling subtle but distinct pressure from a more senior leader – all of which suggest acting now. The leader must mobilize a member of their team, otherwise incur increased business risk. As if enervated by electrical current, the leader sets off at a brisk canter into the nearby office of a direct report, and in an animated, even forceful way says “I need to you to address this issue now, and to the highest standard of excellence… we have to GO.” If we were to pause at this moment we might find that, to the leader, this ‘push’ makes sense. Their rationale feels logical. They’ve amassed data to justify their challenge. They perceive their intent as sound, since they’re pushing someone to do something valuable for the enterprise – not to aggrandize themselves or pursue personal glory. However, at the same time, the team member, unaware of that background information, may be thinking “whoa, where is this intensity coming from?! What’s the context? What’s the leader’s intent? Should I interpret this as a challenge or a threat? Does this represent a personal criticism, did I do something wrong? How do I translate and interpret what I’m seeing?”

This is a common scenario in which a leader needs to challenge, push, or pull someone to achieve a difficult goal. Owing to the intensity, forcefulness, or assertiveness involved in the interaction, and the lack of shared information between the two parties, misunderstandings can arise. One skill leaders can use to resolve such misunderstandings in cases where they want to challenge others to the limit of performance, is signaling.

In this article, I’ll define what signaling is, how it differs from common communication (or ‘cheap talk’), and how leaders can use it to increase others' receptivity towards their challenge.

What is signaling?

Signaling is a term that emerged from the field of economics in the 1970s, courtesy of an academic named Michael Spence. (He received a Nobel Prize in 2001 in part for his work on signaling, along with one of its underlying assumptions, information asymmetry, which I’ll discuss in a moment). His early work in this space touched on how job applicants signal desirable qualities to hiring organizations, by acquiring costly credentials (like university degrees). Later, the concept migrated into the field of management, and spawned volumes of studies exploring how firms and their actors signal to various stakeholders. For example, diversity researchers explored how adding minority Board members signals the organization’s commitment to social values. Many other studies investigated how private firms preparing for initial public offerings (or IPOs) try to signal their underlying quality as a company, by adding prestigious or highly credible Board members or executives to their ranks.

More recently leadership researchers also joined the signaling party. Most of their work touches on how leaders use various kinds of charisma signals to suggest to others that they are in fact competent and have the underlying ability to coordinate the group’s actions.

(Anecdotally, I hear the term signaling used often in the media related to foreign policy and politics. “Emmanual Macron says he will not rule out sending troops to Ukraine, signaling to Russia that he has the capability to escalate involvement in the conflict.” Another one I’ve heard is “Donald Trump/Joe Biden is using his speeches at political rallies to signal his agenda for a second term.”)

So, if signaling has become a ubiquitous term in economics and management, and is seeping into our ideas about leadership, and even into our common vernacular, what is it? Based on what I can gather, signaling involves several key qualities:

- Information asymmetry – Signaling involves one party knowing something the other doesn’t. To quote another Nobel Prize winning economist, Joseph Stiglitz, “different people know different things.” This is information asymmetry.

- Signal cost – There should be some cost to expressing the signal. In economics, this cost seems to be conceptualized as ‘front loaded’ – i.e., people or firms must make an up-front investment of time/energy to secure a credential or attribute, before being able to send a signal based on it. (Again, imagine someone acquiring a university credential, prior to using it to send a signal of their aptitude during a job application.) By contrast, when leaders send signals using their verbal communication, the cost may accumulate after the communication itself. In other words, leaders can send a signal in-the-moment, by saying whatever they want, but they may incur costs later if they misrepresent themselves or don’t follow through on their stated intentions (I’ll unpack this further in the next section).

- Signal observability – The signal must be detectable by the receiver, regardless of the form it takes (e.g., credential/attribute, verbal communication).

- Signal reveals something unobservable – The signal needs to convey something underlying, and hard to discern about the signaler. In most cases this underlying characteristic is ‘quality’ (i.e., whether you’re a high vs low quality leader, or firm), or ‘intent’ (i.e., what the signaler plans to do).

- Beneficial to the receiver – There’s an assumption that the receiver would benefit from obtaining the information contained in the signal.

For leaders, what’s the difference between signaling and ‘cheap talk’?

For leaders, most of their interactions don’t involve incurring some up-front cost before they send out a ‘signaling’ communication. Mostly, they just engage in what appears to be ‘cheap talk.’ They talk about many things, for example, inspiring visions and goals; expectations, standards, and accountability; rewards and punishments; coordinating activities among team members; what’s ethically right vs wrong.

So, is signaling relevant to leaders? I think it is in part because of the concept of ‘penalty costs,’ which involves collecting negative feedback from the receiver after sending the signal. In some cases, leaders may be able to say whatever they want in-the-moment, cost and consequence free. However, when a leader signals an underlying intention using their words, it demonstrates their seriousness, ‘precommits’ them to a course of action, and increases the penalties for behaving in ways inconsistent with that signal.

So, to summarize, talk may be cheap in some cases for leaders, but if they interact with stakeholders repeatedly, and want to preserve their reputation, credibility and relationships, leaders have an incentive to signal in honest ways, and to act consistent with their signals.

How leaders can signal when challenging others

Going back to the scenario portrayed in the opening paragraph, when leaders want to challenge, push, or pull others to their performance limit, to achieve a difficult goal, how can they use signaling to enhance their effectiveness?

At this point, let me just emphasize the riskiness of this situation (which might explain why I think it’s a difficult moment for leaders). When leaders challenge others to the limit, they’re essentially extending a request to partner. “Do you want to do this hard thing I’m asking you to do? Will you sign up for this uncomfortable task? It may suck, but will you go with me?” However, offering this proposal is risky in several ways. The leader may project so much intensity that the team member perceives threat, not constructive challenge. The receiver may perceive the challenge as a personal criticism, and evidence the leader is upset with them. They may think the leader’s forcefulness crossed an invisible ‘line of social appropriateness,’ and feel offended. If the leader stumbles in this interpersonal moment, the team member may withdraw from them, which is the opposite outcome to what the leader intends.

In these ‘challenge’ situations, the leader can send several useful signals to team members, to help those on the receiving end interpret the challenge as constructive and benign, rather than threatening:

- Collective intent: “I’m challenging you on this because it’s in the best interest of the team/function/organization/collective, and it will help make us stronger. I’m not challenging you to realize some goal of personal aggrandizement for myself.”

- Humanistic intent: “I care about you. I care about your well-being. I care about your family. As I’m challenging you to do this difficult thing, I’m keeping your personal welfare in mind, and I intend to take care of you as we work through this.”

- The challenge isn’t personal: “I’m challenging you on this because I’m really focused on resolving this overall issue. This challenge isn’t about you, or your personal performance, and it’s not a critique - you haven’t done anything wrong.”

- Linkage to goals/values/purpose (this approach also depersonalizes a challenge): “I’m challenging you on this because it will help us realize our goals/I’m challenging you on this because it’s something we need to do to stay consistent with our values/I’m challenging you on this because it will help realize our vision as an organization.”

- Context/Rationale: “You haven’t been privy to all the information I’ve already received, the reports, emails, and conversations. But let me help get you up to speed, so you realize the importance of this thing I’m challenging you on.”

- Engagement: “I know I’m asking you to do something difficult right now, but I want you to know you’re not alone. I’m not going to ‘dump and run.’ I intend to be fully engaged on the issue going forward, and to give you whatever support you need.”

- Conviction/Importance of the issue: “I know I’m challenging you to do something difficult, but I want you to know that I’ve really thought this through and I have a high level of conviction that this is the right course of action/I know I’m challenging you to do something difficult, but I want you to know that I have a high level of confidence that this is a really important objective for us to achieve.”

- Standard: “I know we thought this was the standard to aim for, but in fact THIS needs to be our standard of excellence. It’s important that we set this new, higher standard.”

In the signaling examples I’ve given above, I’ve considered a case where a leader is challenging a team member to ‘do’ something difficult yet important. However, sometimes leaders need to challenge ‘thinking,’ not ‘doing.’ When challenging in a debate context, leaders could also consider using the following signals:

- Advanced warning: “I would like to challenge on this issue. Are you ok if I push you harder on this?” (Note this also involves seeking permission/consent, which is another way to mitigate the perception of threat when challenging others.)

- Underlying feelings: “Personally, I am feeling some tension or anxiety about this issue. This whole thing is causing me angst. In light of that, could I challenge a bit harder on it?” (I think this approach also works because it humanizes the signaler through the act of showing vulnerability, which makes it easier to relate to them.)

- Showing constructive intent via offering solutions: “I want to challenge you on this issue, but to show I’m approaching this discussion in a constructive way and that I want to gain traction, I’m going to pair my challenge with a possible solution.”

Intent of participants

You might be reading this and thinking “this idea of signaling sounds like it would work with actors who have good faith intentions to share in a transparent way, but not all leaders or team members possess that intent.”

I agree that signaling as described here may work best when both leader and team member are motivated to reduce information asymmetries. This dynamic probably increases the chances of value-creation in the interaction.

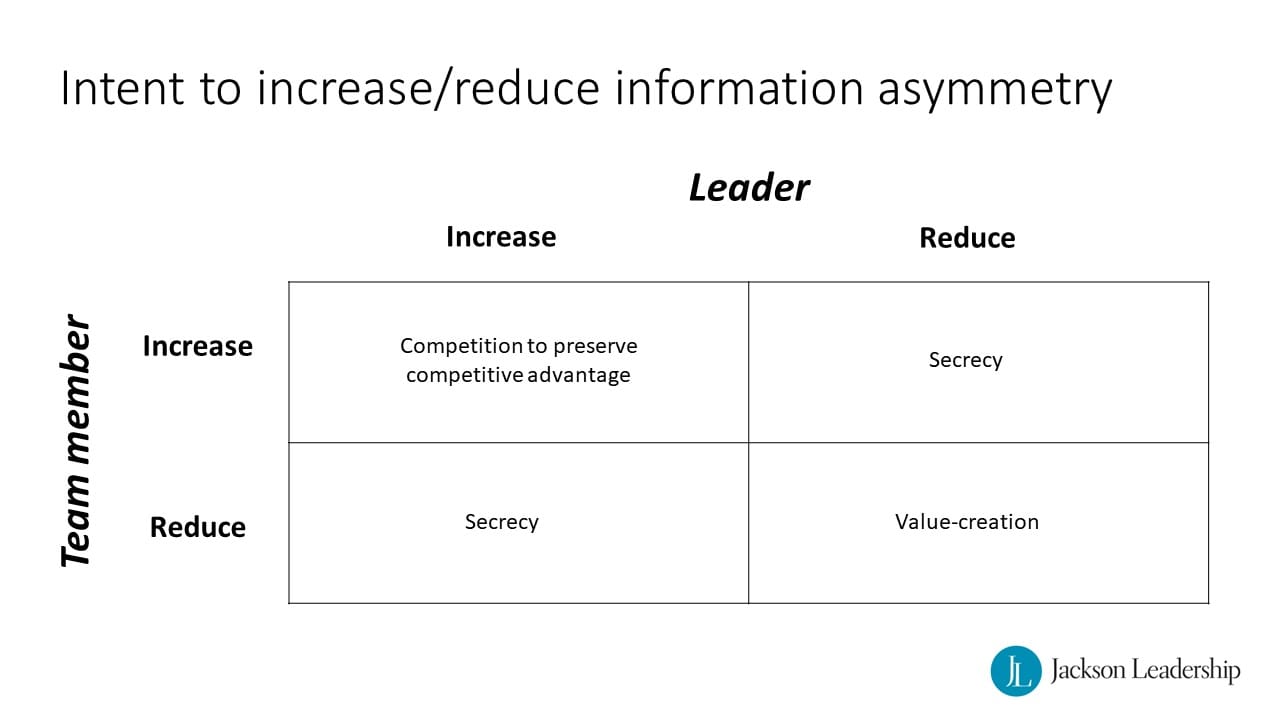

Things may get more complicated in cases where one party, or both, want to increase asymmetry (see the figure below).

What happens if, in a leader-team member interaction, one party wants to reduce information asymmetry but the other wants to increase it? I assume this leads to secrecy from one of the parties. For example, leaders may need to preserve or even increase information asymmetry between themselves and their teams, in cases where some privileged or confidential process (e.g., an M&A) is taking place behind the scenes, and they can’t divulge the details to team members. Team members may also be motivated to increase information asymmetry between themselves and their leader, if it affords them greater freedom of action, or preserves some material advantage (e.g., hiding mistakes to maintain valuable compensation packages).

What happens if both parties want to increase information asymmetry? I’ve seen this most often among leader-peer relationships, where parties hide information from one another to preserve a competitive advantage, or for political/impression management purposes (i.e., to help make the leader look good, while making peers whom they’re compared to, look bad).

Practical application

In general:

- When interacting with 'good faith' actors, and where possible, attempt to reduce information asymmetry using signaling.

When challenging, pushing, or pulling others to reach a high standard of excellence, consider sending the following signals:

- Convey collective intentions, by describing how acting on your challenge will strengthen the broader team, function, or organization.

- Convey humanistic intentions, by telling those you’re challenging that you care for their well-being, and that this remains a key concern of yours despite asking them to do ‘hard things.’

- Convey that the challenge isn’t personal to the receiver, and that you simply want to address the issue.

- Explain how the challenge aligns with the established goals, values, or purpose of the team or even the enterprise.

- Provide all the context and rationale that you can, which the other party may not yet possess.

Conclusion

While leadership is many things, one of its most important functions is helping others ‘make meaning’ out of their experiences. Leaders are sense makers, and sense givers. They help their followers take the raw material of their experience, and sculpt it into a symbolic interpretation that becomes a source of motivation. This kind of meaning making is especially critical when leaders want to challenge for higher performance standards. Team members need to perceive the challenge itself as constructive, and the path to the goal as worthwhile. To do this leaders must convey, and signal, what nuances others must know but don’t. Signaling is one way in which leaders can reveal underlying facts and intentionality, reduce information imbalances through rich communication, and ultimately make meaning that encourages achieving something exceptional.

Tim Jackson Ph.D. is the President of Jackson Leadership, Inc. and a leadership assessment and coaching expert with 17 years of experience. He has assessed and coached leaders across a variety of sectors including agriculture, chemicals, consumer products, finance, logistics, manufacturing, media, not-for-profit, pharmaceuticals, healthcare, and utilities and power generation, including multiple private-equity-owned businesses. He's also worked with leaders across numerous functional areas, including sales, marketing, supply chain, finance, information technology, operations, sustainability, charitable, general management, health and safety, quality control, and across hierarchical levels from individual contributors to CEOs. In addition Tim has worked with leaders across several geographical regions, including Canada, the US, Western Europe, and China. He has published his ideas on leadership in both popular media, and peer-reviewed journals. Tim has a Ph.D. in organizational psychology, and is based in Toronto.

Email: tjackson@jacksonleadership.com

Web: www.jacksonleadership.com

Newsletter: www.timjacksonphd.com

Member discussion